How 7-Inch Vinyl Changed Music and Built Reggae

How a Small Record Format Revolutionized Music & Transformed Reggae Forever

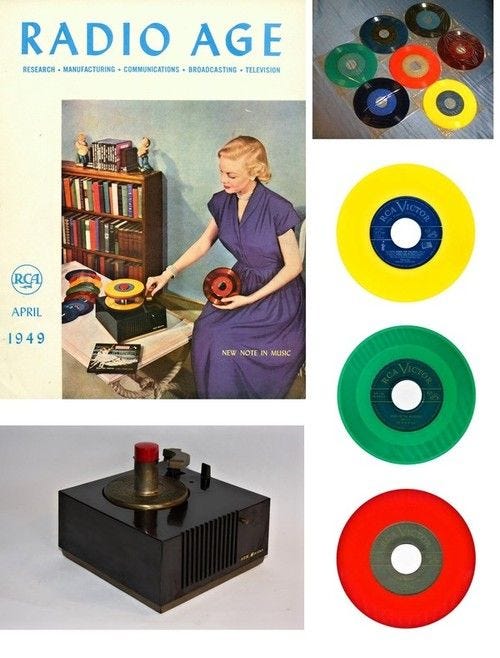

When RCA Victor introduced the 7-inch vinyl record in 1949, no one could have predicted how a small piece of plastic would revolutionize the music industry—and completely reshape the sound and business of reggae.

The Birth of the 7-Inch (45 RPM)

The 7-inch was RCA’s answer to Columbia Records’ 33⅓ RPM LP. Smaller, lighter, and more durable than the old 78s, this new format spun at 45 revolutions per minute and could hold about 3 to 5 minutes of music per side—just enough for one strong song.

It was portable, perfect for jukeboxes, and became the standard for hit singles across the globe. But its real impact came from how it fueled a culture of quick, affordable music distribution—setting the stage for musical revolutions worldwide.

How the 7-Inch Changed Global Music

Cheap to produce: A fraction of the cost of 10" or 12" records

Radio-friendly: Ideal length for airplay and marketing

Singles-first culture: Pushed new artists into the spotlight fast

Jukebox-ready: Dominated bars, diners, and dancehalls

This format encouraged a hit-driven model: test the waters with a single, and if it takes off, think about an album later. That model still holds today—only now it’s on Spotify instead of vinyl.

Jamaica’s Embrace of the 7-Inch: The Heart of Reggae

When American R&B poured into Jamaican sound systems in the 1950s and ‘60s, local musicians started recording their own versions of those rhythms. The 7-inch format became the tool of choice.

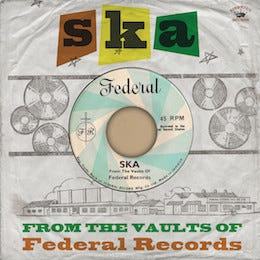

Jamaican pressing plants like Federal Records, Dynamic Sounds, and Sonic Sounds made small-batch 7-inches accessible to independent producers. A single run might be 500–1,000 copies—just enough to test a track at dances and gauge crowd reaction.

Cost to press a 7-inch in Jamaica back then? Around $0.10–$0.25 USD.

This affordability gave rise to a fast-paced, experimental industry where producers like Coxsone Dodd, Duke Reid, and Bunny Lee could release music at an incredible rate.

The B-Side That Changed Everything: Dub Is Born

In Jamaica, the B-side of a single wasn’t just filler. It was where dub was born.

Typically, the A-side featured the vocal version, while the B-side offered a stripped-down instrumental “version.”Pioneering engineers like King Tubby would remix these instrumentals with wild reverb, echo, delay, and dropouts—creating a brand new sonic artform.

This led to the rise of dub as both a genre and a mixing technique. The 7-inch became a blank canvas not just for songs—but for sound design itself.

Dubplates, Exclusives & Sound System Warfare

In Jamaican sound system culture, the 7-inch was more than a record—it was a weapon.

Selectors and DJs would commission dubplates—acetate one-off versions of tracks mixed exclusively for their sound system. These custom cuts often featured personalized lyrics calling out rival sounds or bigging up the selector.

No one else had that version.

No one else could bust that riddim.

Winning a clash often came down to who had the freshest dubplates or the most exclusive 7" pre-release. The street cred and business that followed could make or break a sound system.

Riddim Culture and Reggae’s Business Model

The 7-inch format gave birth to riddim culture—where one instrumental track was used over and over with different singers and toasters. Instead of albums, producers built catalogs of singles all riding the same groove.

This approach:

Maximized studio time

Created hit after hit from one beat

Fueled DJ culture and remixing long before hip-hop

Bunny “Striker” Lee, King Jammy, and others mastered this model, turning the 7-inch into a conveyor belt for hits.

A Lasting Legacy

Though the digital age has taken over, the 7-inch still holds power:

DJs worldwide still spin 45s in reggae, soul, funk, and hip-hop sets.

Collectors and selectors revere rare pressings and exclusive dubplates.

It remains the foundation of sound system culture.

Today artists continue pressing 7" singles for soundsystems, collectors and to hold something tangible in their hands. It’s foundational to the reggae scene and will continue to be for many more decades.

What Was the First Ska or Reggae 7-Inch Release?

Likely Candidate: "Easy Snappin'" – Theophilus Beckford (1959)

Often credited as the first ska record.

Released on Coxsone Dodd’s Worldisc label.

Recorded in 1956 but not released until 1959 on a 7" single.

Featured a heavy offbeat piano rhythm—laying the foundation for ska’s rhythmic bounce.

While “Easy Snappin’” is not the only contender (others suggest Derrick Morgan or Higgs and Wilson also helped define early ska), it’s widely accepted as the first major ska release on 7" vinyl in Jamaica.

First Reggae 7-Inch?

Likely Candidate: "Nanny Goat" – Larry & Alvin (1968)

Released on Studio One.

Considered one of the first true reggae songs—slower tempo, heavier bass, and a clearer move away from rocksteady’s smoother style.

This track helped signal the official transition from rocksteady to reggae.

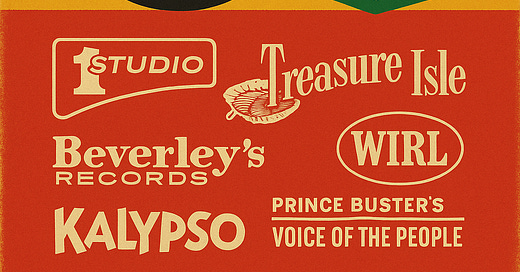

Early Pioneering Record Labels in Jamaica

These labels didn’t just release music—they shaped genres and helped launch careers of nearly every major Jamaican artist.

1. Studio One (Coxsone Dodd)

Started in the late 1950s, often called the Motown of Jamaica.

Released some of the first ska, rocksteady, and reggae records.

Home to Bob Marley & The Wailers, Burning Spear, Alton Ellis, and many more.

2. Treasure Isle (Duke Reid)

Originally a liquor store with a sound system.

Became Studio One’s main rival in the 1960s.

Known for more polished productions—big in rocksteady and early reggae.

Released The Techniques, Phyllis Dillon, The Paragons, etc.

3. WIRL (West Indies Records Limited)

Run by Edward Seaga (future Prime Minister).

Released early Jamaican recordings in ska and mento.

Played a key role in developing the Jamaican recording industry.

4. Beverley’s Records (Leslie Kong)

Helped launch Desmond Dekker, Jimmy Cliff, Bob Marley, and Toots & the Maytals.

Known for clean production and crossover hits like “Israelites.”

5. Tip Top / MRS / Kalypso (Ken Khouri)

Owned Jamaica’s first pressing plant and studio.

Released early mento and calypso in the 1950s, moving into ska by the early '60s.

6. Prince Buster’s Voice of the People

Prince Buster was a producer and sound system boss.

Released fierce, political ska and early rocksteady.

Known for songs like “Judge Dread” and “Hard Man Fe Dead.”

Sound Systems & the 7-Inch Boom

When the 7-inch vinyl began making waves in the late 1950s and early '60s, Jamaica’s sound system culture was already in full swing. These mobile dance parties were the heartbeat of the island’s music scene—and they became the perfect ecosystem for this new record format.

Early Sound Systems that Helped Launch the 7-Inch Era:

Sir Coxsone Downbeat (Clement Dodd)

Duke Reid’s The Trojan

Tom the Great Sebastian

Count Machuki & King Edwards the Giant

V-Rocket and Sir Percy

Prince Buster’s Voice of the People

Ska-Voo-Vee and El Suzie

These systems weren’t just DJ crews—they were music incubators. Soundmen traveled to the U.S. to buy R&B records, then returned to Jamaica to play them at street dances. As local producers began recording their own songs, they pressed them onto 7-inch vinyls, which could be quickly cut, tested live, and replaced if the crowd didn’t move.

The 7-Inch as a Grassroots Business Tool

By the mid-60s, the Jamaican music scene had developed its own feedback loop:

Record a track.

Press a limited run (300–500 copies).

Test it on a sound system.

If it hit—press more and hustle them out.

What made the 7-inch so powerful was its DIY nature. For a few dollars, a singer, producer, or even a soundman could press a tune. You didn’t need a major label or big backing—you just needed a good riddim, a catchy vocal, and access to a pressing plant like WIRL, Federal, or Dynamic Sounds.

Distribution: From Trunks to Shops

There was no formal industry machine—distribution was raw, fast, and local.

Record trunks: Producers and artists often sold 7-inches directly from the trunks of their cars, just like in the iconic scenes from the film Rockers.

Hand-to-hand delivery: Artists would physically bring new releases to shops like Joe Gibbs, Randy’s, or Rockers International—and haggle for shelf space or upfront cash.

Sidewalk vendors: Street hustlers sold records on corners, at dancehalls, or outside sound system events and rum shacks.

Sound system exclusives: Some 7”s were never even sold—only pressed for one selector as a dubplate or early test pressing to hype a new artist or producer.

How This Created a Whole Music Economy

This hustle-first model grew into an entire micro-economy powered by the 7-inch:

Key Roles in the Ecosystem:

Producers – Controlled riddims, booked studio time, paid singers

Engineers – Mixed versions, created dub B-sides

Musicians – Worked across labels, sometimes anonymously

Singers/Toasters – Recorded vocals over reused riddims

Pressing Plants – Created small-batch 7-inches quickly

Shops & Street Sellers – Handled the grind of distribution

Selectors & Soundmen – Decided which tunes became hits

Everyone ate a piece of the pie, and a tune could go from an idea to a Kingston-wide smash within days. This nimble, responsive industry became a proving ground for artists like Toots & The Maytals, The Wailers, Burning Spear, and Gregory Isaacs.

From Street to Global Stage

By the early 1970s, reggae had evolved into an international force—but it never lost its grassroots roots.

Island Records and Virgin began signing Jamaican artists —but the heartbeat remained the street 7” single.

UK-based sounds like Sir Coxsone Outernational, Saxon, and Jah Shaka brought dubplate culture to Britain.

Independent labels in the UK, US, and Europe mimicked Jamaica’s indie 7" model, keeping the format alive.

Even today, many reggae, dub, and dancehall artists still release music on 7-inch vinyl—not just for collectors, but to stay connected to the culture's roots.

It Was Always More Than a Format

The 7-inch record wasn't just a disc—it was a calling card, a business model, a test, and a battle tool. It allowed unknowns to become stars, street-level producers to become moguls, and local dancehall hits to echo across the world.

Like the Rockers film showed: a man with a bike full of 45s could take over the town.

If you have any additional information that you feel important or missing, please share in the comments section below.

This incredible microcosm of vinyl, musician, promoter, and talent churned up a torrent of music that will never be duplicated. I love them all.